From the mid-1990s to the second decade of the 21st century, violent and property crimes decreased significantly in the United States. Austin enjoyed the same decrease in crime rates for the most part, until the last few years. Now the violent crime rate in Austin is higher than the national average (although still low for metropolitan areas), and the property crime rate is now almost twice the national average, and higher than Ft. Worth or Dallas. In some parts of Austin (East Cesar Chavez area) crime rates are almost three times higher than even the Austin average.

What conditions are associated with a high crime rate? Generally, poverty, drug use and alcoholism, gang activity, unemployment, and family violence (affected by all of the above) are associated with higher crime rates. This would appear to be true in the areas of Austin that have high crime rates. The types of crime are different in some areas with high crime rates. Downtown Austin has higher rates of property crimes, and violent crime is higher in the St. John’s neighborhood. Most violent crimes involve people who know each other, with domestic violence, gang activity, and arguments fueled with drugs or alcohol. You can generally avoid violent crimes by maintaining good family and social relationships. Property crimes are the most common type of crime in most areas of Austin. Many property crimes go unreported, and few that are reported are solved. Property crimes are generally random and not targeted, so everyone is at risk.

Why is the crime rate higher In Austin than in some other Texas cities? Like other large cities, Austin has the social characteristics associated with crime: poverty, drug use and alcoholism, gang activity, unemployment, and family violence. Drug use has always been a problem in Austin, probably due to the proximity to Interstate 35 as a major route for drug trafficking. In the past 5 years, a growing homeless population has been associated with higher crime rates in areas of Austin, including downtown (see the blog on Homelessness). Unfortunately, this involves not only property crimes but also targeted and random assaults. For this reason, downtown Austin can no longer be considered safe.

Individuals who are homeless are not committing all of these crimes, but I would argue that their presence in high population density areas contributes to the overall crime rate in those areas. Homeless populations are associated with high rates of illegal drug use. Drug dealers target the homeless, and are associated with organized crime which includes drug trafficking, migrant smuggling, human trafficking, money laundering, firearms trafficking, illegal gambling, extortion, counterfeit goods, wildlife and cultural property smuggling, and even cyber-crime. And if Austin is a great place for you and I to live, it is also a great place for organized criminals.

Since the mid-1990’s the state of Texas and other states in the US have implemented criminal justice reforms reducing sentences for non-violent crimes and increasing the use of probation and community service. In the last ten years, Texas has closed 10 prison units, by not locking up non-violent criminals and by paroling others early.

The increasing crime rates in Texas cities would suggest that this is not working. The recidivism rate for convicts in Travis county is greater than 50% (if you calculate recidivism on re-arrest, not re-incarceration). The old system did not work either, where we spent over $20,000 a year to house low-level offenders, regardless of their risk for recidivism. At the same time, there are individuals who are habitual criminals and they clog the system and deter police from policing low-level crimes. As police ignore and skip the investigation of minor crimes, criminals are committing more bold crimes like robbery because they know police are overwhelmed. And the public is frustrated.

So, what should criminal justice reform look like? Some have advocated that we stop prosecuting minor crimes like drug use offenses. I think that this is a bad idea for a couple of reasons. First, illegal drug use is problematic for the user, their families, and their friends and companions. Second, it has been my experience that one of the best incentives for someone to get help with substance addiction, is interaction with the criminal justice system. I expect that the same is true for other minor crimes like shop-lifting – an interaction with the criminal justice system is likely to correct uncharacteristic behavior.

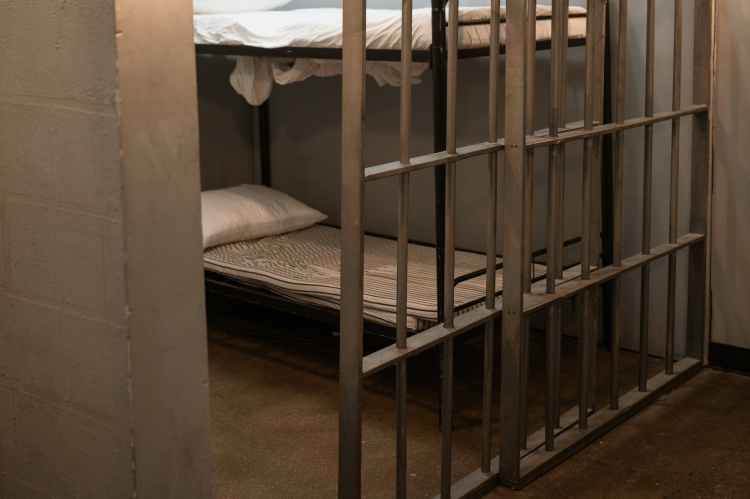

That does not mean that we should go back to incarcerating individuals who commit non-violent minor crimes – we know from history that incarceration doesn’t work either. It has become my opinion that we should rethink the purpose of incarceration. In the past, incarceration has been primarily enforced as a punishment. Secondarily, incarceration protects the public from violent criminals, and also from habitual criminals. I advocate that we should abandon incarceration as a punishment, and reserve it for protecting the public from violent and habitual criminals.

So, how do we punish non-violent crimes? Non-violent offenses should be punished financially and by community public service, with mandatory job training, mental health treatment and substance abuse rehabilitation. Financial penalties would be assessed on a sliding scale based on ability to pay and collected over an appropriate time. For those who are unable to pay financial penalties, community service should be substituted. Financial penalties would fund the criminal justice system and provide funds for job-training, mental health treatment and substance abuse rehabilitation programs.

Current financial penalties are completely inadequate in most cases. Some do require restitution, but that does not repay the cost of the criminal justice system. For example, Martha Stewart was sentenced to 5 months in jail and fined $30,000 for insider trading in 2004. At the time of her sentencing, her net worth was more than $300 million. She saved more than $45,000 on her illegal stock trade. It made no sense to punish her with incarceration at a cost to taxpayers of about $30,000 a year, and it also made no sense to fine her .01% of her net worth. A fine of 1% of her net worth would have provided $3 million for the criminal justice system. Her current net worth Is $645 million. That is how it goes for most white-collar criminals.